To peer or not to peer – online cartels

Anyone who uses the internet receives and sends data through a variety of routers that are interconnected to form networks (autonomous systems). This exchange of data may either take place free of charge or involve charges to be borne by the autonomous systems. And because there is next to no market regulation, it gives powerful autonomous systems opportunities to control the competition and maximize their own profit. One example of this is the cartel formed by Swisscom and Deutsche Telekom that is currently under investigation by the Swiss authorities.

Data is constantly being exchanged on the internet. Anyone who visits a website sends a request to the server that the website content is stored on. The server then sends the website content to the requesting device.

However, this data is not exchanged along a direct route between point A and point B. Instead, the exchange is indirect and takes place through networks of connected routers. So everyone can communicate with everyone else, and everyone essentially has access to all the content available on the internet. These router networks are referred to as autonomous systems (ASs).

The internet is made up of tens of thousands of global ASs that are directly or indirectly linked to each other. The data is sent and received between the different ASs. An AS has a unique global identifier and can consist of just a single router or several thousand routers. AS operators are internet service providers like Init7, which has the AS number AS13030.

Interconnection

Anyone who has an internet subscription with Init7 forms part of the Init7 AS. However, so that Init7 customers can also connect to destinations outside of the Init7 AS, the Init7 AS is linked with other ASs. So the data might flow across several ASs until it reaches its destination. This link between two ASs is called aninterconnection. The data exchange takes place at what are known as the interconnection points, where the ASs connect either using an exclusive fiber-optic cable (PNI Private Network Interconnect) or over an Internet Exchange.

Important interconnection points in Switzerland include carrier-neutral data centers such as Equinix (Zurich) and Interxion (Glattbrugg), not to mention research locations such as CERN (Geneva).

Peering

Peering is a type of interconnection where two ASs exchange data between their respective customers (e.g. email correspondence between Init7 customer X and Swisscom customer Y). No other ASs are involved in the data exchange.

Interconnection involves certain costs for the ASs, but since, with peering, the costs involved are basically the same for both ASs, they usually agree on exchange without charging the corresponding fees. In other words, peering is usually “free”. This is also referred to as “zero settlement peering”.

Transit

However, not all ASs can connect directly with each other – either because they do not share an interconnection point or because the data volume of the interconnection is too small and it is not worthwhile investing in the hardware associated with setting up peering.

In this case, one AS purchases transit services from another AS. This means that an AS does not transmit its data directly to the destination AS. Instead, it sends it through a transit provider, or through an “intermediate AS”, so to speak. The transit provider ensures that the data can be sent (directly or indirectly) to all networks worldwide (by means of its own peering or transit agreements). This generates additional costs for the transit provider, which are paid for by the transit user.

Hierarchy of autonomous systems

ASs are classified according to their size into tier 1, tier 2, or tier 3 networks. There is no official definition of the individual levels and the boundaries are not always completely clear. In principle, the three categories can be defined as follows.

- Tier 1: Network providers at this level operate large, mostly global networks and have to reach all the other Tier 1 ASs through peering (i.e. without them having to request transit connections for data traffic). They offer transit services to smaller ASs.

- Tier 2: Tier 2 network providers include medium-sized, mostly national service providers that can handle a large portion of their data traffic without transit. They are both providers and consumers of transit services. As a tier 2 network provider, Init7 reaches around 65% of all global internet destinations through peering. Init7 handles around 98% of all data traffic through these peerings.

- Tier 3: This includes smaller, mostly regional service providers or companies that have no direct peering connections and rely solely on transit.

Who pays for the traffic?

With conventional telephony, the “calling party pays” principle applies. The person who makes a call (i.e. requests data) also pays for it. If this principle is applied to the internet, the end customer is the “caller”, as they are the one requesting data (e.g. a Netflix video). This means that the end customer is the initiator of the data traffic, not the content provider.

Nevertheless, the aforementioned zero settlement peerings without charges have become established and are used almost everywhere. This is because it makes no difference which peering partner sends the larger amount of data, as the infrastructure costs do not depend on the direction the data is flowing in. So traffic is “free” because each partner bears its own costs. This benefits both parties, as both save money with respect to transit costs (“mutual benefit”).

How some network providers exploit their power

However, some major internet providers have reversed the “initiator pays” principle and demand money for peering from content providers like Netflix and others (turning the “calling party pays” principle into “sending party pays”). The reason for this is that the amount of data that the content provider sends far exceeds the amount of data that the end customer sends, even if the end customer requests the data.

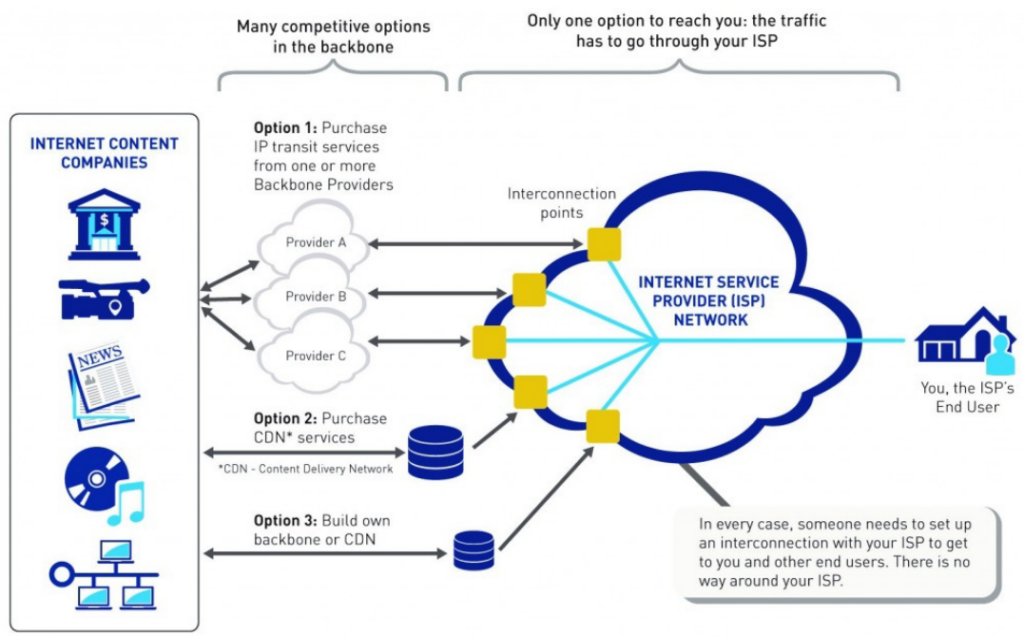

This principle can be enforced because internet providers have a technical monopoly on their end customers. Regardless of where the traffic ultimately comes from, it must always pass an interconnection point (marked in yellow on the diagram) on the way to the provider’s end customer. At these interconnection points, the network provider has the power to act like a kind of bouncer. Only those who have passed the “security check” are allowed in. To make access more difficult, some network providers do not adapt interconnection capacities to the actual needs. In other words, they ensure that the lines are overloaded and that the data gets stuck in the queue (passive-aggressive behavior). This results in videos that keep buffering. So content providers may be forced to pay money to increase capacity.

Size Matters

The larger a network provider, the more likely it is that they can exploit this technical monopoly. But regardless of their size, many major network providers in Europe and globally have become more convinced that they should take full advantage of this situation. They kind of put a gun to the content provider’s head and say: “Pay for paid peering or your data will have to wait in line!”. Smaller network providers like to team up with larger ones to extort more money from content providers. If this reminds you of a mafia movie, you wouldn’t be entirely wrong.

#Netflixgate

In spring 2016, there was a well-known case of this type of blackmail in Switzerland that made headlines under the hashtag #Netflixgate.

Netflixgate was triggered by satirist Viktor Giacobbo with the following tweet.

.@Swisscom_Care Gedenkt ihr, endlich das Netflix-Problem zu lösen – oder soll man zur Konkurrenz wechseln? @NetflixDE @Swisscom_de

— Viktor Giacobbo (@viktorgiacobbo) March 20, 2016

Translation: @Swisscom_Care Do you intend to finally solve the Netflix problem – or should we switch to the competition? @NetflixDE @Swisscom_de

At that time, Swisscom refused Netflix zero settlement peering, intending to force it to use paid peering. But Netflix was not impressed by this in the slightest and made customers in the Swisscom network wait in a data queue, leaving them to stew in a haze of pixels. To cut a long story short, after just five days Swisscom gave in and agreed to zero settlement peering with Netflix. It was genuinely worried that broadband customers would leave in droves and switch to its competitors.

So size definitely plays a role for a content provider, and a global, popular provider like Netflix can certainly bring a medium-sized (in a global context) provider like Swisscom to its knees. Smaller content providers with less popular offerings that are only of interest to a specific group, for example, have to meet the monetary demands that large providers make or abandon their business model. Alternatively, they can take the arduous and lengthy legal route. Swisscom tried to force Init7 to pay peering fees in 2012. After a civil court ruled that it had no jurisdiction, Init7 submitted an application for interconnection with Swisscom to the Swiss telecoms regulator, the Federal Communications Commission (ComCom), in March 2013.

The Swisscom and Deutsche Telekom cartel

During the proceedings, it became apparent that Swisscom and Deutsche Telekom had entered into agreements that virtually force other ASs to send their data to Swisscom through Deutsche Telekom’s fee-based transit services.

A detailed explanation of how this works is provided below.

Content providers such as Netflix or Zattoo are expected to send large amounts of data to their customers when they watch videos. If the customers have internet subscriptions with Swisscom, the content providers must somehow send their data to the Swisscom AS.

In theory, this would be possible through peering (either directly to Swisscom or through other ASs). However, Swisscom does not agree to free peering. Instead, it charges content providers fees for the data, because it claims that the ratio between the amount of data sent and the amount of data received is extremely asymmetric.

Content providers could send your data to Swisscom indirectly through other ASs. But since Swisscom exclusively uses Deutsche Telekom as a transit provider for its large private customer base, the data will sooner or later flow through its network as long as there is no direct peering between the content provider and Swisscom.

As a “solution”, Deutsche Telekom offers content providers fee-based transit services to the AS of its “vassal” Swisscom, which in turn benefits from Deutsche Telekom’s size and increases its market power. In addition, Swisscom receives a cut of the income from the forced paid peering from Deutsche Telekom in the form of reimbursements. And Deutsche Telekom can force double payment, because it already receives money for the connection from broadband customers.

So content providers have no choice but to pay fees to send their data. And Swisscom collects money either directly through paid peering or indirectly through Deutsche Telekom. At the same time, end customers pay for being able to receive data through the subscription charge. Comparing this to telephoning, both the caller and the person called would have to pay for the call. Not only is this annoying. It is also contrary to antitrust law, because the technical monopoly means that Swisscom has a dominant position on the market.

The interconnection proceedings

As mentioned above, Init7 was, in its role as a transit provider for content provider Zattoo, subject to this kind of blackmail by Swisscom in 2012. At that time, Swisscom limited the required peering capacity to around 20% of the previous data volume without prior notice. This meant that Init7 could no longer transmit Zattoo data in the desired quality and that Zattoo users were left with a haze of pixels. Zattoo was forced to buy peering capacity from Swisscom at short notice, causing Init7 to ultimately lose Zattoo as a customer. So Init7 demanded that ComCom make a decision on cost-based interconnection with Swisscom under Article 11 of the Swiss Telecommunications Act (TCA). The actual costs are CHF 0.00, which corresponds to zero settlement peering. In July 2018, ComCom rejected Init7’s request because it believed that Swisscom did not have a dominant position on the market, contrary to the opinion of the Competition Commission (COMCO). Init7 appealed against this decision to the court of appeal, the Federal Administrative Court (BVGer). In its ruling in April 2020, the BVGer overturned ComCom’s decision and referred the case back for reassessment.

Finally, on December 19, 2024, following expert opinions from the parties Init7 and Swisscom, a new opinion from COMCO and an assessment by the price watchdog, ComCom decided in Init7’s favor. Swisscom must bear the costs of the proceedings, amounting to more than CHF 170,000. However, the decision is not yet legally binding. It is to be expected that Swisscom will lodge an appeal against ComCom’s decision with the BVGer and prolong the proceedings further.

ComCom’s 90-page ruling can be summarized as follows:

- Swisscom holds a dominant position on the relevant market (access to its own end customers – resulting from the aforementioned technical monopoly), including for the period from 2016 onward. So Swisscom must guarantee cost-based access (i.e. interconnection).

- Interconnection (peering) and IP transit are indispensable upstream services for end customers’ internet connections.

- According to the Swiss Telecommunications Act (TCA) and the Swiss Cartel Act (CartA), ComCom is responsible for ensuring competition by means of regulatory measures in case of a provider’s market dominance, otherwise smaller providers would have no chance of entering and becoming established on the market.

- The direction of data traffic (incoming or outgoing) is irrelevant for cost accounting.

- In the vast majority of cases, traffic from content providers is caused by end customers (e.g. when they request a YouTube video). End customers already pay for the broadband connection and cover the costs incurred.

- The actual chargeable costs of the interconnection relate only to the router ports and the cable between the two peering partners. As both partners have to bear their own costs (amounting to the same sum), the monthly fee owed is CHF 0.00, which corresponds to the zero settlement standard.

- Swisscom is not permitted to refuse necessary upgrades. An upgrade is required at a volume of 50% of the nominal capacity. The standard measure is the 95th percentile method that is commonly used within the industry.

The ComCom ruling is to be considered a tremendous success that will have implications far beyond the parties to the proceedings in Switzerland. Regulators abroad will scrutinize the decision. Hopefully, content providers elsewhere will institute similar proceedings against the abusive market power of incumbents and other major access providers. However, there are political lobbies that aim to achieve exactly the opposite. Although ETNO, the European association representing incumbents, has recently given itself the harmless name “Connect Europe”, it is in actual fact an extremely tough lobbying organization in the European Parliament and continually tries to influence legislation for the benefit of its clientèle. How this works is demonstrated by the efforts of some ETNO members, as described below.

Content providers should invest in network expansion

In February 2022, four of the EU’s largest internet providers demanded that content providers cover some of the costs of the fiber-optic rollout, because they claim that the content providers are responsible for the majority of the data traffic. However, this demand is unjustified because, ultimately, it is these internet providers’ end customers who are responsible for the data traffic. They request the data by clicking on a video’s “Play” button. And the network and content providers are reimbursed for sending the data through the relevant subscription fee. How the EU will deal with the demand is currently unknown. However, the providers’ lobbyists seem to be quite successful with their fabricated narrative. So it is all the more important for ComCom to be the first European regulator to issue a decision against the monopoly position that the large providers occupy.

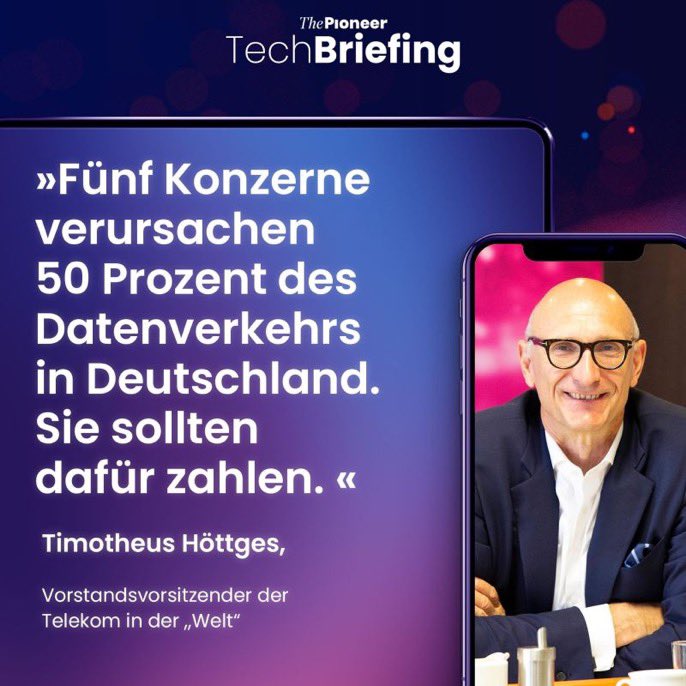

Translation: “Five companies account for 50% of data traffic in Germany. They should pay for it.” Timotheus Höttges, Chairman of the Board of Management of Deutsche Telekom, in “Die Welt” newspaper