Reading time: 13 minutes

Switzerland’s “Fiber Optic Dispute”

The “fiber optic dispute” is an important antitrust case that happened in Switzerland – a case of enormous economic significance. In a nutshell, Swisscom, the largest telecommunications provider in Switzerland, attempted to monopolize fiber optic infrastructure in the country, but it was prevented from doing so by the “Cartel Act”, the Swiss Antitrust Law. In this blog, we’ll summarize how this case came to be and where fiber optic technology is headed.

Liberalization of the telecommunications market

In 1998, the telecommunications market underwent a liberalization process in Switzerland. The former agency PTT (Postal Telegraph and Telephone) split to become Swiss Post and Swisscom; the latter company was later listed on the stock exchange in Switzerland and the USA. However, legislators at the time liberalized the industry relatively half-heartedly, as the Swiss Federal Government retained and still retains a majority shareholding in Swisscom (2/3 back then and 51% today). Instead of completely separating telecommunications infrastructure (copper networks and switchboards), which should have remained 100% controlled by the federal government, and the business-to-customer entity, which should have been completely privatized, the government decided to maintain the status quo; consequently, the conflict of interest as legislator, telecommunications’ regulator, and majority shareholder remained. This conflict of interest has persisted to this day and is largely responsible for the fact that numerous political issues in the telecommunications industry are still unresolved. These issues pop up on the Swiss political agenda from time to time – most recently with Swiss National Councilor Balthasar Glättli’s postulate in 2017.

ADSL gets popular

Around 2001, ADSL (Asymmetric DSL) telephone networks were rolled out on a large scale in Switzerland, mainly for private end customers, alongside conventional DSL (Digital Subscriber Line) networks. However, only ex-monopolist Swisscom had access to copper cable networks, often referred to as local loops. All competitors – referred to in technical terminology as TSPs (telecommunications service providers) – had to try to assert themselves on the market, purely as wholesale product BBCS (Broadband Connectivity Service) resellers, which some of them failed to do. Companies like Callino, Riodata, Econophone, Tele2 and Telefonica were active at the time, but have all since disappeared as independent brands. They either went bankrupt or were taken over by other providers.

A particular problem with DSL reselling was the fact that the market leader used what’s known as the “margin squeeze” method in their sales. There wasn’t enough of a margin offered between its own “Bluewin” brand retail prices and the BBCS wholesale prices to allow competitors to operate cost-effectively. Margin squeeze is illegal under antitrust law. Sunrise, a telecommunications competitor, subsequently reported Swisscom to the Swiss Competition Commission; however, the proceedings were very lengthy, as Swisscom appealed against every decision. This legal process led all the way up to The Federal Supreme Court in Switzerland, which only reached its final verdict in 2020; Swisscom was ultimately sentenced to pay an antitrust fine of CHF 186 million. In addition, Swisscom reached an out-of-court agreement with Sunrise to pay several hundred million francs in damages; however, the exact amount was not disclosed.

The Telecommunications Act’s first revision

In the mid-2000s, the Swiss Government realized that there was no way around further restricting Swisscom’s privileges in order to ensure functioning telecommunications competition in Switzerland. The revised Telecommunications Act (TCA) then came into force in 2007. In particular, the law stipulated regulating the local loops, i.e., the copper lines, from the switchboards to the end customer. This made it possible for Swisscom’s competitors to install their own DSL infrastructure in the switchboards and, therefore, bring ADSL services to the market independently of Swisscom. However, Swisscom did everything possible to put a stop to this new form of competition. Excessive prices, complicated processes, and lengthy delivery times: the regulator ComCom (Federal Communications Commission) and the OFCOM (Federal Office of Communications) had their hands full trying to force Swisscom to be reasonably cooperative.

The infrastructure competition doctrine

The doctrine that telecommunications competition has to be based on infrastructure competition still prevails in Bern today. In the 2000s, this idea was somewhat plausible because, in addition to the conventional copper networks for telephony, many regions had a co-axial (co-ax) cable network for distributing TV signals. This network was equipped with a return channel and increasingly used for the delivery of Internet connections. Co-ax cables are technically superior to copper cables; with the latest DOCSIS version 4.0, a downstream speed of up to 10 gigabits/s is possible with a co-ax cable. The best-known co-ax network provider was the former company Cablecom, which later operated under the name UPC and merged with Sunrise in 2020 to become the largest alternative telecommunications provider in Switzerland. Fun Fact: Swisscom held a third of Cablecom’s shares over 20 years ago, but it had to sell them due to antitrust concerns.

Although infrastructure competition was justified in the 2000s, it has become pretty outdated from today’s perspective. This is because both the cable and telephone companies are currently only building FTTH fiber optics (fiber to the home) to replace co-ax and telephone networks. So, the two network infrastructure systems merged into one. However, the Swiss National Council and the Council of States often still dream of the bygone era of infrastructure competition, justifying their political decisions as a result.

Fiber optic roll-out begins

Starting around 2006, various Swiss cities began to roll out fiber optic networks, as it became clear that FTTH would mean significant benefits for municipalities. Municipal energy suppliers were the perfect means of laying fiber optic cables due to their existing pipeline infrastructure for supplying electricity, as fiber optics are more resistant to interference from magnetic fields in comparison to copper cables. Fiber optic cables can therefore be installed in the same ducts and pipes as electrical cables.

A few of these major projects were approved in Swiss federal referendums (called “popular votes” in Switzerland) over the last approximately 15 years. In Zurich, the city’s population first approved a loan of CHF 200 million for a fiber optic project in 2007, followed by another one totaling CHF 400 million five years later. A similar popular vote in Winterthur was held comparatively late in November 2012. However, this delay didn’t end up being a bad thing: A quick roll-out made up for the wait. Winterthur currently has one of the densest FTTH networks in Switzerland, covering 99% of the population.

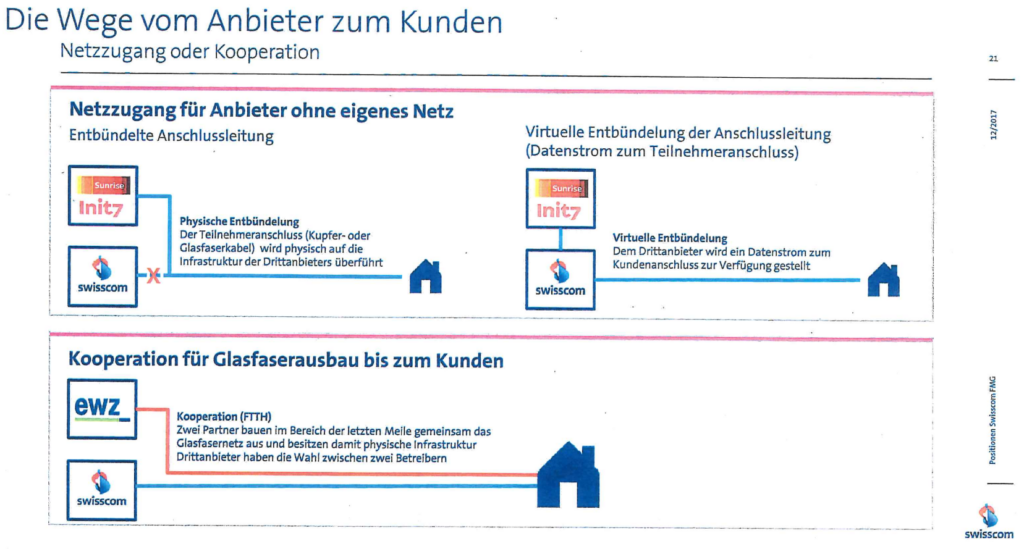

Needless to say, Swisscom didn’t want to be left behind, and it began building FTTH infrastructure throughout the country. In order to avoid buildings being connected twice – by the local electricity supply company (ESC) and by Swisscom – an agreement was quickly reached to establish “fiber optic cooperation.” City districts were usually divided up between Swisscom and the respective ESC, depending on the existing pipeline infrastructure, in order to carry out the network expansion as efficiently and cost-effectively as possible. However, the Competition Commission had to intervene because the first version of these cooperation agreements violated antitrust law. The two cooperating parties had agreed upon clauses that would have created a monopoly or duopoly. The problem still hasn’t been completely resolved to this day – even after the COMCO’s ruling. ESCs always claim that they’re in fierce FTTH competition with Swisscom in their respective market areas; in reality, however, they enjoy a comfortable collective market dominance situation in which both players move in unison and hardly get in each other’s hair.

The Roundtable – technical standards and the 4-fiber model

The OFCOM followed these developments closely and anxiously, as there was a risk that every fiber optic provider could be left to their own devices. Zurich’s ESC , “ewz”, in particular felt justified in rapidly expanding the grid to its liking following the positive outcome of the first popular vote. The OFCOM therefore invited all fiber optic stakeholders to a Roundtable in Biel for the first time in 2008. Subsequently, several teams developed technical standards and rules on how fiber optic infrastructure should be built. Under “gentle” pressure, everybody involved finally agreed “voluntarily” to stick to these self-regulation rules, which essentially comprised the 4-fiber model (each residence is connected with 4 optical fibers), a uniform numbering scheme, and P2P point-to-point network topology. In most areas, the cooperating partners each received different optical fiber strands: fiber strand 1 for the ESC and fiber strand 2 for Swisscom; fiber strands 3 and 4 were used almost everywhere as a reserve, and they were only built from the OTO (Optical Termination Outlet) socket to the BEP (Building Entry Point) or drop cable. The cable to the switchboard (feeder) was therefore only created for fiber strands 1 and 2. This is referred to as a 4-4-2 (in-house – drop cable – feeder) expansion; in some places, only a 4-4-1 expansion was set up.

The Roundtable’s success

In retrospect, this self-regulation method has turned out to be very successful, which the OFCOM mentions on its website. Each TSP, i.e., each provider, managed to install their own electronics in the switchboards and, therefore, gained access to the optical fiber going straight to the end customer. This model, commonly referred to as open access, enables increased levels of innovation and competition. Technically, bandwidths of 100 gigabits per second are already possible today; whether this makes commercial sense is, of course, open to debate. The fastest offer currently available for private customers is 25 gigabits per second – this is our Fiber7 product.

The Telecommunications Act’s second revision

As the decade went on, it became clear that the TCA would have to be revised again, in particular because services linked to local loops were becoming increasingly uncompetitive, as the length of copper cables determines their bandwidth. In other words, the longer the cable, the slower the speed – with an exponential decrease. Swisscom therefore opted for fiber optic feeds to street cabinets in residential areas in order to shorten the copper cables and achieve adequate bandwidths (VDSL, G.fast) – even in areas that were far away from the switchboards. Competitors weren’t able to cover the costs of this investment due to their low market share, so they switched to the BBCS wholesale product. Swisscom was happy with this outcome, as it allowed the company to predetermine broadband competition in terms of both technology and price. An industry insider once mockingly referred to the phenomenon as “competition by Swisscom’s good graces.”

The number of unbundled local loop connections has fallen rapidly since reaching a peak in 2012. The need for high bandwidth and advances in technology resulted in concerns about regulation. FTTH fiber optics were still completely unregulated, although well over one million households and businesses were connected to FTTH by 2018. This is why the Federal Council called for technology-neutral regulation in its report on the TCA’s latest revision. Doris Leuthard, the former Head of the Federal Department of Environment, Transport, Energy, and Communications (DETEC), said the following during a debate in the Council of States:

“Over the past few years, the Federal Council has refrained from legislating because we have reached an agreement with the industry not to slow down fiber optic investments […]. We have established rules at a Roundtable with various stakeholders, for example, the rule […] that four-fiber optic cables should be installed so that various providers have access to these technologies while keeping costs down.”

However, the Swisscom lobbyists managed to persuade the Council of States to remove the article on technology-neutral regulation from the proposed legislation. The revised TCA, now in force since 2021, is a somewhat pointless initiative from a competition perspective; it’s essentially based on the assumption that Swisscom will behave in a compliant manner and not get in the way of its competitors. Federal Councilor Leuthard believed the assertions that the Roundtable’s fiber optic rules would continue to apply.

Swisscom misleads the Federal Government

As soon as the technology-neutral regulation had been completely removed from the agenda in parliament, Swisscom announced it would be constructing FTTH for a further 1.5 million households by 2025 in February 2020, albeit with a modified network topology. Instead of using the P2P network topology agreed upon at the Roundtable, the company decided to use P2MP Point-to-Multipoint networks (see our blog entry ‘The difference between P2P and P2MP’). Swisscom wanted to monopolize fiber optics by using the network topology it had built to determine which electronics were suitable for competitors. In addition, P2MP is only profitable if a provider achieves a mid-double-digit market share. This would have forced smaller competitors to resell their pre-assembled BBCS products or leave the market altogether. From an antitrust perspective, it was clear that Swisscom was abusing its dominant market position, as the agreed upon “open access” concept would have been blocked by the P2MP network topology. Therefore, just three weeks after Swisscom’s announcement in February 2020, the COMCO (Competition Commission) launched an initial preliminary investigation.

Init7 files a complaint

After more and more FTTH connections using the new network topology came onto the market, which no longer supported Init7’s preferred products, Init7 filed a complaint against Swisscom with the COMCO in September 2020. The Swiss German television program “10 vor 10” gave a report on the problem shortly before it happened.

The COMCO’s precautionary measure

The COMCO opened proceedings just three months after the complaint and issued a precautionary measure against Swisscom on December 14, 2020. With immediate effect, Swisscom was no longer allowed to build and market FTTH connections based on P2MP network topology. This was because Swisscom could have created a “fait accompli” situation during the presumably long-term proceedings. The COMCO therefore confirmed the risk of distorting competition in the Internet connection market. Considering that FTTH fiber optics will most likely be in operation for decades, it would have been fatal for the Swiss economy to simply allow Swisscom to establish a fiber optic monopoly.

Swisscom ignores the COMCO

In January 2021, Swisscom filed an appeal against the COMCO’s decision with the first appeal instance, the Federal Administrative Court (FAC) in St. Gallen. The FAC then invited representatives from the COMCO, Swisscom, and Init7 to a hearing.

Appeal rejected

Swisscom’s appeal was rejected by the Federal Administrative Court on September 30, 2021 in an extremely clear 219-page ruling. It also stated that the collaborative decisions made at the Roundtable were still valid and that an important market player such as Swisscom shouldn’t be allowed to break the rules so easily Even the argument claiming that P2P is “much” more expensive than P2MP was picked apart by the FAC. Additional costs of a maximum of 20% were tolerable, as the Roundtable had already been aware of these costs and Swisscom itself was highly committed to the four-fiber model at the time.

Following the FAC’s ruling in October 2021, Swisscom stopped marketing around 93,000 illegally built FTTH connections. However, the connections that were already in operation weren’t switched off.

Swisscom ignores the COMCO’s and the FAC’s decisions

Despite the ongoing proceedings and the order to stop constructing P2MP network topology, Swisscom persisted with its plans and installed a total of over 600,000 FTTH connections using the illegal construction method. A good proportion of these connections are still in operation, although an increasing number are being blocked today. Swisscom’s stubborn stance of not backing down from its monopoly prevents several hundred thousand households and businesses throughout Switzerland from being able to connect fiber optics to their buildings, as they aren’t allowed to use the topology and still have to rely on copper cables.

New complaints from Swisscom

Swisscom decided to appeal what it considers to be an unfavorable ruling by the Federal Administrative Court to the second and final appeal instance, the Swiss Federal Supreme Court (FSC) in Lausanne. The company asked to repeal the precautionary measure in order to be able to continue building P2MP connections during the ongoing multi-year legal proceedings. The FSC rejected the application on December 6, 2021. But Swisscom didn’t accept this ruling either and continued expanding its P2MP connections anyway.

Swisscom CEO Urs Schaeppi is forced to resign

In February 2022, Swisscom announced that its CEO, Urs Schaeppi, would be stepping down – in exchange for a generous severance package. He was CEO for nine years and, therefore, primarily responsible for attempting to monopolize the fiber optic network. In October 2022, his successor, Christoph Aeschlimann, announced that Swisscom would resume building FTTH fiber optics according to the P2P network topology and that some of the connections blocked by the legal dispute would be converted to P2P. It’s noteworthy that Swisscom’s management admitted this despite the fact that the case was still pending before the Federal Supreme Court; apparently they had realized too late that they were flogging a dead horse.

The precautionary measure is confirmed in the final instance

On November 2, 2022, the Federal Supreme Court confirmed the precautionary measure taken against Swisscom. Expanding and marketing fiber optics using P2MP network topology has been permanently prohibited for the company.

Feeder Cleanup

In December 2022, Swisscom sent out a list for the “Feeder Cleanup” project, announcing that around 36,600 illegal connections would be converted to the compliant construction method in around 110 switchboards. However, this conversion process will take at least two years to complete. A few months later, the company admitted that it would not only partially switch to the legal P2P system, but would do so completely.

Closing the main legal proceedings

While the proceedings regarding the interim measure were concluded by the Federal Supreme Court with legal effect, the main proceedings took several months before the final decision was reached. Last fall 2023, the 170-page application submitted by the COMCO Secretariat to COMCO was presented to all parties to the proceedings for consultation, and COMCO also held a hearing on November 20, 2023.

COMCO’s decision was announced on 25.04.2024. Swisscom must pay an antitrust fine of CHF 18.4 million and may not monopolize the fibre-optic network. The modest amount of the fine is irritating due to the long history and the lack of understanding shown by those responsible. However, it is important that COMCO remains firm and issues guidelines for the expansion of fiber optics so that innovation competition is not hindered. Swisscom will definitely be prohibited from building and marketing a P2MP network topology. The approximately 750000 illegal connections that have already been created must be converted or switched off by the end of 2025. However, Swisscom has already announced that it will appeal against COMCO’s ruling. This means that the proceedings are likely to take several more years while the courts, i.e. the Federal Administrative Court and the Federal Supreme Court, deal with the appeal.

Comments

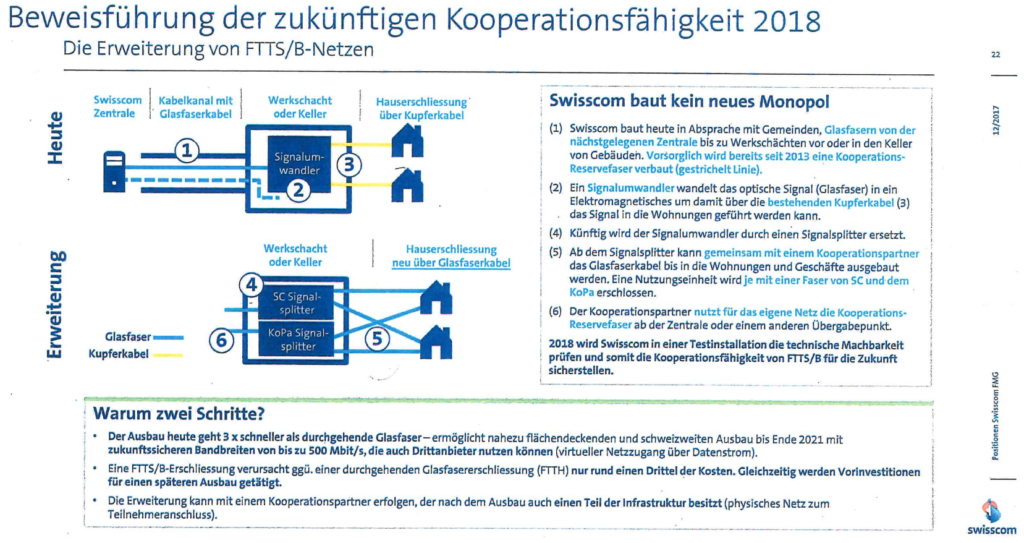

Although Swisscom was “victorious” after the Telecommunications Act’s second revision by convincing the majority of the Council of States to remove the technology-neutral regulation from the draft bill, this victory came at a heavy price. What’s more, the company’s plan to switch to P2MP network topology, which would distort competition, was already clear to insiders at Swisscom at the beginning of 2018. We know this from their “secret plan” document entitled “Reasons for future cooperation capabilities.”

Another cause for concern is that, although Swisscom is majority-owned by the Swiss Confederation, the Swiss Federal Council, with its laissez-faire policies, failed to exert any pressure on the Swisscom Board of Directors to develop their infrastructure in the best interests of the Swiss economy. The federal representative on the Swisscom Board of Directors seemed to be acting as a puppet.

The political parties in Bern also seem to be relatively indifferent in general. The Social Democrats are happy to pocket Swisscom’s annual dividend of CHF 22 per share and have failed to recognize that fiber optic infrastructure is a public service worth protecting – one that shouldn’t be left to neo-liberals to safeguard. On the other hand, the Radical Free Democratic Party, free-market believers, hasn’t understood that only strict regulation in the wholesale market can ensure maximum competition in the retail market. One Member of Parliament from the Swiss People’s Party was particularly irrelevant with his argument that Swisscom is a “good company” that sponsors several sporting events throughout the country.

Switzerland’s “fiber optic dispute” was – in addition to an enormous loss of time, with countless people and companies having to wait longer for fiber optic services – also really expensive. Converting to P2P-compliant architecture is likely to cost Swisscom around half a billion francs. In addition, the company will have to deal with unrealized income due to the precautionary measure imposed by the court and, ultimately, the antitrust fine. It’s a curious thing that the people responsible at Swisscom’s Board of Directors and the Executive Board got off scot-free; moreover, ex-CEO Schaeppi was paid a severance package of CHF 1 million.

Even the Swiss Government has to face the accusation that failed regulations in the TCA’s revisions made the “fiber optic dispute” possible in the first place. The fact that the “botched” Telecommunications Act had to be patched up with the Antitrust Law doesn’t speak for the Council of States’ foresight, which – against the Federal Council’s, the ComCom’s, the OFCOM’s, the National Council’s and the entire telecommunications industry’s wishes – blocked the regulation. We can only hope that the TCA will be revised for a third time in the new legislative period to make up for the omissions made during its second revision.

Glossary

COMCO

The Competition Commission’s tasks include combating harmful cartels, supervising the abuse of market-dominant companies, carrying out merger controls, and preventing state restrictions on competition and inter-cantonal trade.

Source

OFCOM

The Federal Office of Communications is responsible for telecommunications, media, and postal services in Switzerland; it also ensures stable and advanced communications infrastructure. The office is part of the Federal Department of Environment, Transport, Energy and Communications (DETEC).

Source

FAC

The Federal Administrative Court (FAC), based in St. Gallen, is Switzerland’s general administrative court.

Source

FSC

The Federal Supreme Court (FSC), based in Lausanne, is the highest judicial authority in Switzerland. Along with the Federal Assembly (legislative branch) and the Federal Council (executive branch), it embodies the third state power of the Swiss Confederation, the judiciary (judicial branch).

Source